|

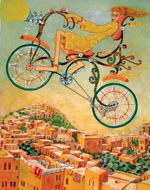

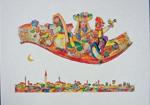

| |  | | Artwork by the late Hassan Hourani. |  | |  | | Artwork by the late Hassan Hourani. |  | | Artwork by the late Hassan Hourani. |  | |

The Last Bard: Palestinian Folktales, Children’s Stories and Sleeping Rituals

By Ali Qleibo

Kan Yama Kan, once upon a time, when the basil and lilies were in the lap of our Prophet Al-Adnan (nickname for Prophet Mohammed, Peace be upon Him), there lived Haroun Al-Rashid, a wise king very different from the kings of these days. “Zubeidah was the beloved wife of the Caliph Haroun Al-Rashid. She was bold, beautiful, and wise.”

This One Thousand and One Nights tale of the jealousy of the glorious Caliph of Baghdad was one of my sister’s and my favourite bedtime stories. We would have to be in bed by 7:30, and the story was the final rite in the nightly sleeping rituals. The visit to the bathroom, brushing the teeth, and the washing followed soon after supper. Mom would supervise all the steps until she tucked us in bed, turned off the lights, and read verses from the Qur’an to lull us to doze off. But we would stay awake in bed, resisting sleep, waiting for dad’s return from the café. We were eager for the one final story we knew he would tell us when he got home.

Historical allusions mixed with fictionalised personas to conjure a primordial time of bliss. The otherness lying beyond the here and now and far removed in time and space provided a distant world to which we would journey aloft on the magic carpet of words. “Aladdin and the Magic Lantern,” “The Thief of Baghdad,” “Badr Al-Budoor,” and most of our other bedtime stories were gleaned from classical Arabic literature: One Thousand and One Nights, Kalilah wa Dimnah (the eleventh century Arabisation of the Indian Panchatantra), and stories of the prophets’ lives.

In time, when we had acquired the art of reading, these classics in expurgated versions provided our first forays into the magical world of books. As we grew older, our childhood became peopled with the heart-breaking misadventures in Pinocchio, Tom Sawyer, Gulliver’s Travels, Alice in Wonderland, and dreams of friendship, as in Le Petit Prince. These novels became our constant companions, keeping us awake late into the night. The magic inspired by our early childhood bedtime stories developed into a passion for books, the taste for which evolved through time.

Bedtime rituals vary among Palestinians, reflecting the heterogeneity of our cultural identity, which has deep roots in the patterns of early Canaanite patterns of settlement. The urban, peasant, and nomadic communities had different approaches to sleeping patterns and story telling that were delineated by the collective structure of the household, and the corollary design and function of the single room/tent residence. As opposed to the literate urban centres such as Gaza, Nablus, Jaffa, and Jerusalem, the rural populations were, until recently, predominantly illiterate and depended on oral forms of transmitting knowledge. Folktales, riddles, anecdotes, maxims, and jokes were employed as children’s bedtime rituals. The oral discourse, the body of literature that museumologists refer to as “folklore,” provided the collective pedagogical tools through which folk precepts and wisdom were passed on. Corollary to the social, religious, economic, moral, and ethical precepts that changed both over time, and from one community to another, diverging narratives were deployed. The spoken word was woven into a suspense drama and set to music, and provided reflexive critical cultural expressions through which the current political, economic, religious, and ethical values were deconstructed.

Kan ya ma kan, through alliteration and anagrammatic innuendos, the introductory cliché to the folktale is the magic carpet with which our imagination journeyed into a dreamland whose end was indicated with the idiomatic phrase, tutu tutu khilset al-haddutu.

To need, to wish, to desire, and to dream are important elements in which hope is forever renewed and the means by which individual identity is realised. To the question, hilweh willa mattutu, is it a good or bad story, we would barely nod in approval, for we would have already drifted into deep sleep.

The different architectural structure, layout, designs, functional use, furniture, and lighting of dwellings, caves, and tents reflected the different relationships that urban, rural, and nomadic Palestinian communities had to oral narratives. Whereas the urban house would be composed of several rooms to which specific functions were assigned, including individual bedrooms, the structure of the Bedouin tent or the traditional multifunctional peasant single-room dwelling excluded the possibility of putting the children to sleep alone in their room and diminished the possibility of bedside stories. Traditionally among peasants, everyone slept side by side, each on his/her mattress in the single room housing the four-generation extended family. One was born, lived, and died surrounded by people. The design of the Bedouin tent, though different from the peasant multifunctional single-room dwelling, also reflected the collective life of its inhabitants. “The tent is partitioned into separate apartments (shiq, from which the Arabic word shuqqah for apartment is derived).” Ibrahim Salameh, my Bedouin friend from Beer Sheva, explained, “The women slept with the children in a separate shiq, and the men had their own shiq, which was within the same tent but separated by curtains.” A longitudinal shiq at the front of the tent served as the public space and provided the hearth where guests, tribesmen, and the male members of the clan were received, entertained, and regaled with coffee, music, and poems that the bard wove into the fabric of the lyrical epics extolling chivalry and love.”“Folk tales are mostly narrated in the summer season,” Um Husni explained. “This is the season in which we moved from the village to the fields.”“The carpet of the summer is expansive,” Abu Husni explained, using the Arabic proverb, “bisat al-seif wase,” meaning that people could sit outside in big social gatherings comfortably. Abu Husni continued, “There we would pass the evenings visiting each other and would guile the night telling stories, jokes, riddles, and singing while the young men tended the fields lit by the star-studded sky. The good narrator captured the attention of the audience through his charm and wit. Moreover he had to have a good voice to sing, to act, and to play a musical instrument be it a lute (na’i) or a lyre, (rababeh).”Palestinian sleeping rituals differed according to urban, peasant, and nomadic cultural attitudes towards sleep, and the sense of individuality and private space. Rural life was collective. The urban ritual of preparing children for sleep with a bedtime story or with verses from the Qur’an was not common in either the village home or Bedouin tent once the infant was weaned. Accustomed to falling asleep to a bedtime story, the urban child reads on his own once he reaches reading age. In fact, urban children of a certain socio-economic cultural background are trained to be alone, to cherish privacy, and to develop an independent discourse with themselves as mediated and structured by European and American books in English or in Arabic translations. Peasant and Bedouin lifestyles stress the collective pattern, leaving little space for individual self-exploration and, by extension, reading.In summer in Tarqumia, first, second, and third cousins casually drop by on an almost nightly basis. Together they enjoy the long summer night, exchanging stories, maxims, parables, riddles, and humourous anecdotes. They narrate folktales such as the adventures of Nus Nsis, the picaresque adventures of the Bedouin Swelem and Swelmeh, and the woes and misfortune of Djbeneh. Poetry, heroism, wit, virtue, love, hate, jealousy, envy, loyalty, treason, truth and falsehood, jinn and ghouls, fantastic animals, and supernatural beings are the elements with which the crafty narrator weaves the twists and turns of the plot; the change of fortunes; and the final triumph of love, valour, and virtue into suspense drama. It is a one-man show in which words, gestures, dance, music, rhyme, and cadence provide peasant entertainment. Whereas urban children are sent off to their own rooms at bedtime and whenever visitors drop by, rural children stay up with the adults until they fall asleep. They are covered with a blanket and left in their place until they wake up the next day.“In the fields, the children stay the night with us. The pattern is similar to that established in the village where they follow the daily serialised Turkish, Egyptian, and Syrian soap opera until they fall asleep on the couch,” Um Husni described. “There are no set rules for sleeping hours, studying, school, homework assignments, or for waking up. They manage to make it through school.”Until six decades ago, professional recitals of the Palestinian folk stories were performed for men by specialised bards in the village guesthouse, al-madafeh, or in the cafés catering to rural clientele in the city. Professional bards travelled from village to village, and from one Bedouin camp to another. As the men sipped their bitter coffee, the Bedouin bard enraptured the listeners with tales of bravery, raids, looting, chivalry, and love. The thematic conflict reflected their tribal skirmishes over water and grazing fields, providing a mirror image of their tribal life style. Unlike peasant narratives, Bedouin plots do not make reference to jinn, fantastic animals, or supernatural events. The recital is performed to the accompaniment of the rababeh or na’i, and to the gurgling murmur of the water pipes. The repertoire would include epics such as Kulaib and Zeer, Abu Zeid el Hilali, and ‘Antara and Abla.Alternately the bard would go from home to home to perform for individual families in return for pay. I was barely 12 when I last saw an itinerant bard. He came to my grandmother’s winter house in Jericho, and she did not send him away but let him play as charity. I was young and ignorant, and having been brought up in a French school, could not relate to either the image or to the screeching lyre music and strange voice. I had not yet realised that the heroism of Achilles and the adventures of Odysseus were crafted by a genius who had gleaned his narratives from bards not dissimilar from the Bedouin on our veranda.The birth of Palestinian national awareness was paralleled with the celebration of childhood as a social category to which pioneering intellectuals ascribed a new dimension, image, and identity. Their literature implicitly imputed to childhood romantic ideals, such as the predisposition to favour the concrete over the abstract; the infinite over the finite; nature over culture, convention, and artifice; and freedom and spontaneity over constraint, rules, and limitations. In this vision inspired by Jean Jacques Rousseau’s novel Emile, the children were believed to prefer feeling to thought, emotion to calculation, imagination to literal common sense, and intuition to intellect. A close-up painting of a child’s face with tears trickling down his cheek, which adorns many Palestinian walls, sums up this simplistic view of the fragile purity of childhood.The desire of the Palestinian Ministry of Education to provide Palestinian children with extracurricular storybooks that they can read at home is fraught with difficulties. The nationally endorsed competitions launched for children’s books have failed to produce works that could engage the interest of the Palestinian child. Non-governmental childhood centres and printing houses produce insipid books. According to a former Palestinian minister of education, most Arabic children’s books are badly written, badly illustrated, or badly produced. Often they are all three, especially Palestinian children’s books.“Haroun Al-Rashid wanted to test his wife’s fidelity,” Dad’s tender voice reverberates in my mind despite the distance in time. “So he commissioned a very handsome slave to stay by her side as help. Wherever Zubeidah moved, he followed her, providing constant assistance and staying close to her. In obeisance to the Caliph’s instructions he would rub his shoulder against hers or touch her accidentally with his thighs or hand. Zubeidah became attracted to the slave but was wise enough to realise that the advances were a ploy. She spoke to her husband and asked him to relieve the slave of his duty and gently admonished the Caliph of the Muslims, ‘It is not wise to test the person one loves.’”The magic of Baghdad; the humanity, vulnerability, and frailty of the Great Caliph; and his love for and jealousy of his Zubeidah sparked our love of adventure and life and our compassion for humanity at large. A plethora of books nourished our journey from childhood through adolescence to maturity, and provided lifelong friendship. Dr. Ali Qleibo is an anthropologist, author, and artist. A specialist in the social history of Jerusalem and Palestinian peasant culture, he is the author of Before the Mountains Disappear, Jerusalem in the Heart, and Surviving the Wall, an ethnographic chronicle of contemporary Palestinians and their roots in ancient Semitic civilisations. Dr. Qleibo lectures at Al-Quds University. He can be reached at aqleibo@yahoo.com. See PDF www.thisweekinpalestine.com/i193/pdfs/article/the_last_bard.pdf

| |